February 2023 Monthly Letter

Dear Reconcilers,

This month’s letter is written by Willard High, Pastor Emeritus. We are pleased and honored to share it with you.

“Unacknowledged History”

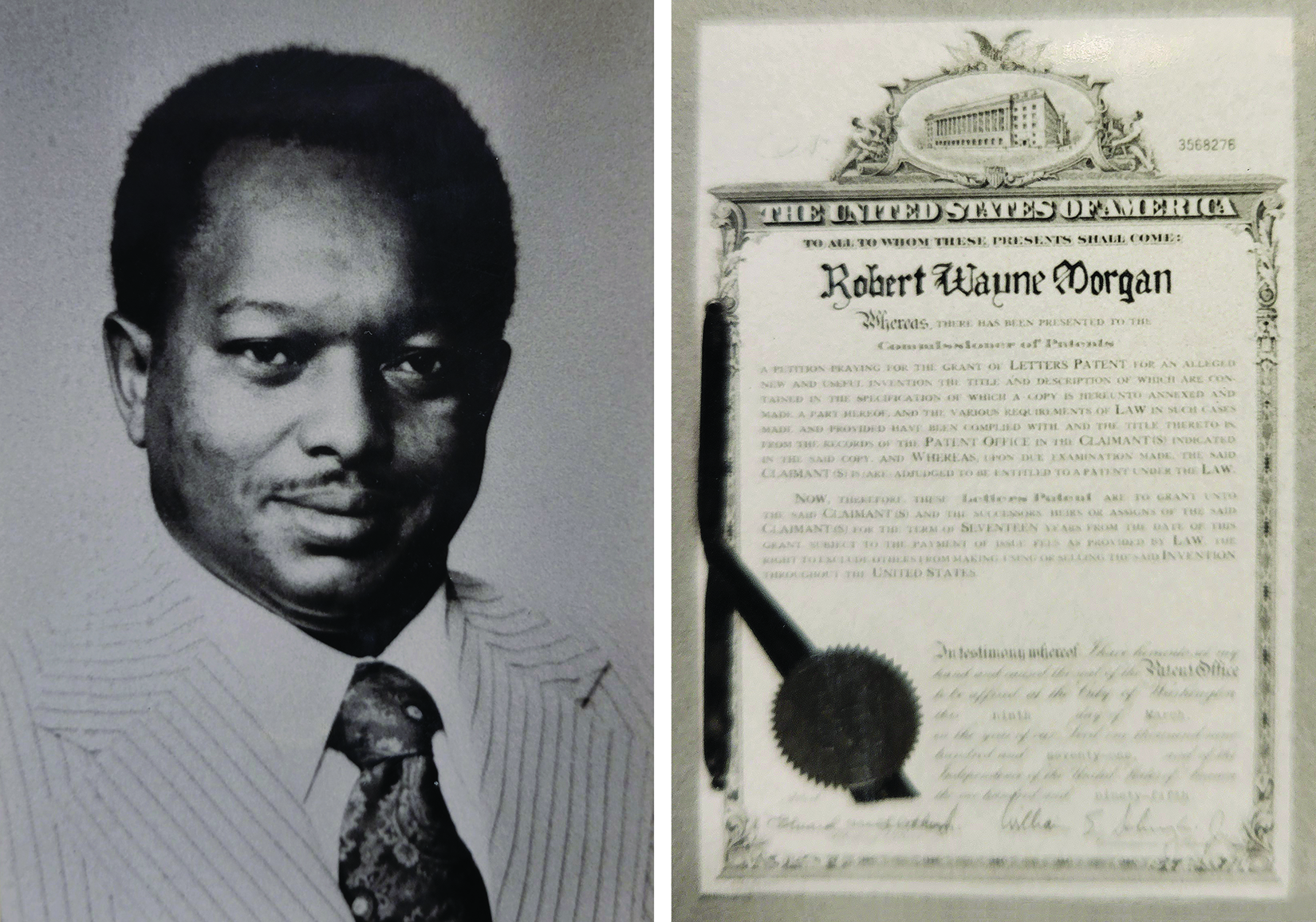

February is Black History Month, a time to recognize the innovation and contributions of thousands of African-Americans, including my “Uncle Billy”— born Robert Wayne Morgan, in rural North Carolina in 1933. He was a decorated veteran of the Korean War. He entered the Military as an 11th grader and was honorably discharged. He went on to finish high school and graduated in 1957 from The American Academy of Funeral Services, Inc., where he became proficient in Embalming, Anatomy, Pathology, Bacteriology, Chemistry, Restorative Arts, Funeral Directing and Mortuary Administration. He married my maternal aunt (Minnie) in 1961.

When I was 12 my mother died and I chose to live with my Aunt Minnie and Uncle Billy, who had no biological children. Uncle Billy became the director of Hodge-Morgan Funeral Home, one of two funeral homes in my home town of Zebulon, North Carolina. Black funeral homes were highly respected in the Black Community during the 1960s as magnets for intellectuals, entrepreneurs, movers and shakers. I regularly listened in on conversations and debates on government, education, civil rights and other subjects. A man of keen intellect and drive, my uncle would often engage me in deep discussions.

Seeking greater opportunity, Uncle Billy and Aunt Minnie left the Jim Crow South in 1965 for Worcester, Massachusetts. There he performed embalming and supervised autopsies. They say, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” My uncle invented and patented an autopsy aid he called the “Zipp-O-Seal.” His invention made opening and closing bodies (which was necessary in autopsies and preparation of autopsied bodies for burial at the funeral home level) a breeze!

Unfortunately, he quickly discovered there is no hiding place from discrimination in America. Even with almost unanimous approval for his invention from funeral homes and pathologists in Worcester, he was systematically locked out of the widespread use and marketing for his device. The Department of Pathology at a major hospital where he had supervised autopsies discontinued use of the Zipp-O-Seal when one of the directors discovered the ethnicity of its creator. When Robert inquired why, he was told simply that the director “did not like it.” Many of the hospital supervisors credited my uncle’s assistant (who was white) for the invention, even though he denied having created it. After arguing that my uncle could not have invented the device, one department head stormed off and returned a few days later with a smirk, insisting the device had been invented in Russia one year prior. In one of many discrimination complaints he filed, my uncle observed that this person would rather credit a Russian with the invention than a Black American. An administrator from another hospital, who was blocking use of his invention, told him that he was using the specialized re-sealable container (designed for storage of surgically removed organs) as a laundry bag at his house. The degree of disrespect and disdain among these individuals is obvious.

My uncle was a very confident person. This undoubtedly made those who stood in his way feel justified in “putting him in his place.” Uncle Billy died in 1980, never having received genuine acceptance from the leaders of the funeral and forensic science industries he had served so energetically and faithfully his whole life.

Black history month was established to correct inequities related to recognition of African-American achievements. The contributions of these Americans have not been acknowledged; instead their intellectual property has often been stolen, or their work and names buried, even while we benefit from their inventions. I appreciate the opportunity to share my Uncle Billy’s story, to honor his innovative spirit, and to highlight his important contribution to funeral and forensic sciences.