February 2013 Subscriber Letter

Greetings ORM Supporters,

February is Black History Month in the United States. Yet our joint commitment to reconciliation crosses all borders. Reconcile Editor Neil Earle, a Newfoundlander, tells this story in his hometown Duarte, California newspaper.

“A naval disaster off Newfoundland’s south coast during World War II shone a little-known light on the uphill American struggle with racism. On February 18, 1942 Mess Attendant Third Class Lanier Phillips’ ship, USS Truxton, ran aground on the jagged coast of Newfoundland’s Burin Peninsula.”

“The ship’s stern was ripped clean off, her bulkhead caved in. One hundred and ten of her crew eventually perished between the towns of Lawn and Saint Lawrence. Lanier Phillips, a native of Georgia, was the only African-American to survive. His name has entered into the legend of a dramatic rescue. He is remembered semi-humorously as the sailor who ‘might have had his skin rubbed off’ by one of the volunteer ladies charged with scraping oil from the helpless survivors, if his race had not been spotted. But the undiscriminating kindness showed to him by the people of the St. Lawrence area that dark day in 1942 would prove to be a life-changing event for Mess Attendant Phillips.”

“Lanier Phillips was the great-grandson of slaves. He could never forget the Ku Klux Klan’s scary parades and their burning down the only black school in town. On that fatal morning in 1942 he found himself stranded on the broken deck of the Truxton with four other ‘colored’ folks—three blacks and one Filipino.”

“Their main topic of discussion was whether they should try to make it to shore or wait for the U.S. Navy to come get them. Rumors had gone out that on the last trip to Iceland the Truxton’s black sailors had been forbidden to come ashore. Iceland once had strict laws against such things. Now, as the waves crashed about the doomed Truxton, five men held a life-and-death discussion on the ruined hulk: Should they go ashore? Would this be like Iceland? How would they be received?”

“Lanier Phillips decided that even if he was threatened with a lynching (a chance he rated highly) he could make a better fight for it on shore. He boarded the last lifeboat and huddled on the beach where white men on ropes were clambering back and forth over the rocky cliffs lifting stranded sailors to the heights above. ‘A white person wants me to live,’ he was thinking through semi-delirium. Later, in a makeshift infirmary, he was scrubbed clean, given dry clothing and bivouacked with a St. Lawrence family. But he still could not sleep. ‘It wasn’t the cold that kept me awake,’ he said later.

‘It was fear. Fear that I would soon be discovered and killed.’ The long reach of racism still bedeviled the Truxton’s lone African-American survivor.”

“The next day he woke to a new reality: He was given a bed, fed breakfast, treated as an equal by people he never knew. Even then his mind worked overtime: ‘This is Iceland…no blacks will be left alive, just like Georgia or Mississippi.’ But after breakfast with his hosts, he was asked to pose for a group picture. Most in Lawn/St. Lawrence had never seen a black man in person.”

‘Did I die? Go to heaven?’ Lanier later recounted. He made a silent vow: I am alive because people helped me. I am worth something as a man, as a human being. ‘There hasn’t been a day past I don’t think about St. Lawrence,’ he said later, ‘They changed my entire philosophy of life.’

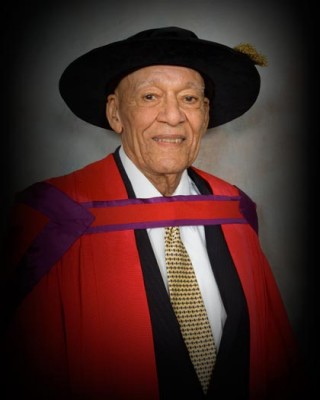

“Back home on leave he was almost beaten up when he found himself sitting ‘too far up’ in the bus. He was forbidden to eat in a diner that was hosting German-Italian prisoners of war. The St. Lawrence experience gave him strength. ‘I knew I’d been brainwashed, told I was inferior.’ Determined to learn a trade, he graduated in 1957 as the first black sonar technician working with people such as Jacques Cousteau and helping locate a lost nuclear bomb off the Spanish coast. In 1966 he ended his navy career teaching antisubmarine tactics. After marching with Martin Luther King at Selma, Alabama in 1965, and speaking against racism at schools and naval gatherings, he was honored with an honorary degree in Newfoundland for his fight against racism.”

What a story! But we are all foot-soldiers in the war against prejudice, for that struggle will never cease. May Lanier Phillips’ story inspire us.

Thank you for your continuing support as Jesus moves us forward.

Love to all,

Curtis